Fact-checking Keith Schembri

25 April 2023

The Maltese parliament’s Public Accounts Committee is investigating the National Audit Office report on matters relating to the contracts awarded to Electrogas Ltd. Former OPM chief of staff Keith Schembri has been summoned to testify before the Committee. His first hearing was on 28 March 2023.

On how a gas-fired power station became a part of the PL’s manifesto

Schembri claimed the Labour party works as a “pyramid scheme” with the Prime Minister at the top, and that it was up to him to delegate duties or pledges for people to implement, without others knowing of such decisions. When asked by the PAC board whether the PL’s proposal on a gas-fired power was formed the same way that other electoral proposals were, Schembri said that he has no idea, he doesn’t know, and he doesn’t remember (“M’ghandix ideja, ma nafx ma niftakarix”.)

Schembri’s claims on the extent of his involvement in the decision to include the gas power station in the party’s manifesto are inconsistent.

When testifying in the public inquiry on 14 December 2020, Schembri had said that he had total control over the PL’s 2013 electoral campaign and that he was involved in several of the party’s policy working groups, including the energy working group. He said that Konrad Mizzi (later, Muscat’s energy minister) was not a member of the PL’s energy working group and that the other members were energy experts and not people in business. (See official transcript, page 85).

Yet, during the PAC hearing on 18 April 2023, after claiming not to know or remember anything on the matter, Schembri said that the idea to include the power station in the party’s manifesto was Joseph Muscat’s, but the power station itself wasn’t Muscat’s idea and he (Schembri) didn’t need to explain further.

When pressed, Schembri also said that the power station proposal was adopted through the same “pyramid scheme” as the other proposals. (PAC: “tahseb li inhadmet - igifieri inti semmejtli il-pyramid scheme - tahseb li inhadmet bl-istess mod ili inhadmu weghdi ohrajn jew inkella di kellha mod differenti kif inhadment? Schembri: “Le l-istess.”)

Schembri also said that Konrad Mizzi and David Galea collaborated with him on the costings of the power station project as did Louis Grech, and that “everything also included the Prime Minister”.

On why he opened his company in Panama

Schembri said: “I did not know Panama was a tax haven. I didn’t ask any questions about it”.

The Republic of Panama is one of the most well-established tax havens in the Caribbean region. Extensive legislation regulates its offshore jurisdiction and financial services sector.

Given Schembri’s familiarity with the Caribbean region through his ownership of an offshore company in the BVI, and with his familiarity with offshore companies’ purpose generally, it is unlikely that he would not have known that Panama is a tax haven.

Schembri held offshore companies in the British Virgin Islands (Colson Services Ltd.), in Gibraltar (Malmos Ltd.), and in Cyprus (1/3 of the shares in A2Z Consulta Ltd through Colson Services Ltd.). He set up Colson Services Ltd in the British Virgin Islands in 2011. It was undeclared and then restructured in 2013 for additional secrecy by hiding his name behind nominees.

His claim that he didn’t ask why Panama was chosen for his company contradicts his sworn testimony in the public inquiry on 14 December 2020. Page 40 of the official transcript quotes him saying (emphasis added): “I needed an asset company and the decision of my auditors was to choose Panama because it is the fastest jurisdiction in which to open a company.”

On the banking set up of his New Zealand trust and Panama company

Schembri said his money was going to go to New Zealand, not Panama, that the Panama company was going to “open everything in New Zealand” and that its bank account would also be opened there.

The Panama Papers data shows that Keith Schembri (and Konrad Mizzi) attempted to open bank accounts in Dubai, Panama, and other Caribbean states and were turned away because they were politically exposed persons (PEPs). The data does not extend beyond December 2015 and so does not include information about Schembri’s (and Mizzi’s) later attempts to find a receiving/transfer base for financial payments.

Keith Schembri attempted to open an account at FBP Bank in Panama in August 2015. On his KYC (know your client) form, he gave his occupation as “adviser” and “not chief of staff to the Prime Minister of a member state of the European Union”, despite being a PEP (politically exposed person) under the law. Karl Cini of Nexia BT emailed the KYC form to Mossack Fonseca on 20 August 2015 by, along with a certified true copy of Schembri’s diplomatic passport. (Konrad Mizzi also tried to open an account at FBP Bank.)

In February 2016, Schembri and Mizzi were in the process of setting up bank accounts with The Winterbotham Merchant Bank in the Bahamas. The process was disrupted when their ownership of secret companies in Panama and trusts in New Zealand was exposed.

Schembri attempted to open accounts in at least eight banks (emphasis added):

Mossack Fonseca first approached a Dubai bank, but were rebuffed after the bank expressed concerns that the two men were Politically Exposed Persons. The law firm then turned to another six banks, the AFR claims: FPB Bank and BSI Bank in Panama, Bank of Saint Lucia International (BOSIL), Winterbotham Trust in the Bahamas, and the Miami branch of Brazil’s Itaú Bank and Brickell Bank. They also talked to Cidel Financial Group. The law firm then turned to BSI bank, but were told that Dr Mizzi and Mr Schembri would have to apply for immigration visas for Panama to open a bank account. — Panama Papers: Two more banks approached for Mizzi and Schembri, Times of Malta, 18 April 2016

The information was first reported by Australian Financial Review on 13 April 2016.

On the set up date of the Panama companies

Schembri claimed he opened his Panama company first before Konrad Mizzi opened his, and that the significant date is when he “ordered” the company and not when it was set up.

Tillgate Inc. (Schembri’s company) was opened on 15 July 2013 and Hearnville Inc. (Mizzi’s company) was opened on 9 July 2013. Schembri said he “ordered” his Panama company in 2015. (Schembri is agitated when he talks about the company dates.)

On the purpose of Panama companies, Tillgate Inc and Hearnville Inc

Schembri said that the Panama companies Tillgate Inc and Hearnville Inc were not opened for the same purpose (“Ma kienux ghal l-istess skop, dik zgur”.)

This is untrue. The identical purpose, set up, and target clients of both companies were detailed in an email Nexia BT’s Karl Cini sent to Mossack Fonseca on 17 December 2015. The document is in the Panama Papers data.

Schembri said Nexia BT only informed him he needed a Panama company after he had already opened a trust in New Zealand.

Schembri’s testimony about the sequencing of his New Zealand trust and Panama company is inconsistent. In the same hearing he also said: “I was told I could only open the trust [in New Zealand] if I also opened an offshore company.”

Schembri first claims he never gave his express consent to Nexia BT to open a Panama company for him, then says he doesn’t remember whether he asked Nexia BT to open a company in Panama for him.

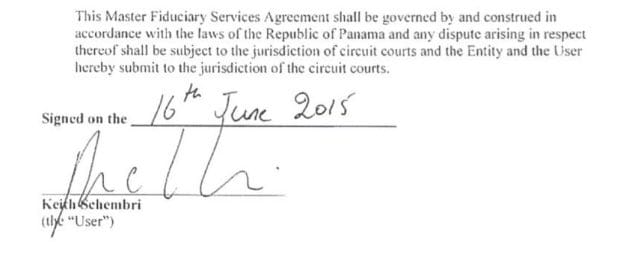

Schembri is known to keep close control over his interests. His claim that a company was opened in his name in a jurisdiction he did not choose and without his prior approval is not credible. The claim is contradicted by documentary evidence. Schembri authorised the opening of a bank account for his Panama company. Furthermore, he signed a Master Fiduciary Services Agreement on 16th June 2015, which states that the agreement “shall be governed by and construed in accordance with the laws of the Republic of Panama”. The signed document is among the 11.5 million financial and legal records investigated in The Panama Papers, an international journalism project published on 3rd April 2016. The documents were leaked from the Panamanian law firm, Mossak Fonseca, which set up Schembri’s Panamanian company, Tillgate Inc.

Schembri said the Panama company was set up for future business plans, once he left government. Schembri said that he was planning on leaving politics in 2016 but he does not remember when he first approached Nexia BT.

Schembri was appointed OPM chief of staff in March 2013. The Panamanian company Tillgate Inc. was set up in 2015. Schembri took over Tillgate Inc. in 2016. He finally left office in November 2019, three and a half years after taking over Tillgate Inc. According to his sworn testimony in the public inquiry on 14 December 2020, when he disappeared from the political scene in late 2016, it was for medical reasons - in other words, it was not for “future business plans”. (See page 54 of the official transcript).

On good governance and PEPs’ business interests

Schembri refused to be drawn on whether it is acceptable for a sitting minister to seek business income while in office. He said he saw “nothing wrong” in Mizzi’s interest in seeking out ways of carving out a post-political future and saw nothing strange in a minister asking for financial advice, nor did he deem it necessary to report to the prime minister that Mizzi’s midas touch” remarks to the prime minister (“kull ma tmiss jsir debb, xi nrid naghmel?”)

Using public office to enrich oneself is the definition of corruption. As the prime minister’s chief of staff Schembri was morally obliged to proactively prevent such activity by advising the prime minister accordingly.

Schembri said that he never wanted to make money from government.

Eight years after his trust and undeclared offshore company, which was structured for secrecy, were exposed, Schembri has yet to provide a credible alternative explanation to the commonly held view that they were set up for illicit activity.

Schembri claimed he took a step back from his business interests while in government. Asked about his Bangladesh company, he says it is ongoing. He has another company that is doing business in Bangladesh.

Keith Schembri did not relinquish his shareholding in any of the companies he set up. His father, Alfio, replaced him as director in Kasco Holdings and its subsidiaries.

On the existence of Muscat’s kitchen cabinet

Schembri dismisses claims that there was an inner circle within the Prime Minister’s office that took certain decisions.

Testifying under oath on 12 August 2020, former finance minister and current Central Bank governor Edward Scicluna said there was a ‘kitchen cabinet’ in Muscat’s government. He identified its key members as Joseph Muscat, Keith Schembri, and Konrad Mizzi. (See pages 2 & 4 of the official transcript).

On his relationship with 17 Black

Schembri claimed not to remember whether he spoke to Muscat and Mizzi about the identity of 17 Black’s owner after Times of Malta and Reuters revealed it was Electrogas co-owner, Yorgen Fenech.

Under oath, Schembri said he informed Joseph Muscat about the identity of 17 Black’s owner himself. This is documented on pages 51-53 of the official transcript of his 14 December 2020 testimony in the public inquiry.

Schembri said it was a “coincidence” his Panama company was opened in tandem with Mizzi’s company, and that it is also a coincidence that 17 Black was going to be the main target company of both Hearnville Inc. and Tillgate Inc.

This is untrue. On 17 December 2015, Karl Cini at Nexia BT sent an email to Mossack Fonseca in Panama. The document is part of the Panama Papers data leaked from the Panamanian law firm, Mossack Fonseca. Times of Malta published the email on 18 April 2018. The subject line references Tillgate Inc and Hearnville Inc. The information Cini provided in the email referred to both Panama companies simultaneously. The email concerns the companies’ activities, main suppliers, expected number of transactions and their amounts, and other details, and it identifies 17 Black and Macbridge as their main target clients.

Schembri claimed he did not write the email.

His claim is disingenuous. The email was from his auditor, acting on his behalf.

Schembri denied knowledge of the content of emails from Nexia BT’s Karl Cini to Mossack Fonseca concerning Panama companies Tillgate Inc. and Hearnville Inc. and associated bank accounts, and denied discussing the matter with Cini. In one email, Cini says he had “spoken to the clients” about the process. Schembri denied that this referred to him.

Schembri’s claims are unrealistic. His business relationship with Nexia BT goes back several years. He maintained that relationship throughout the years of revelations from the Panama Papers, and even after the publication of the 24 June 2020 Times of Malta article detailing the content of Cini’s emails. It is not credible that he maintained a business relationship with someone who ostensibly misrepresented him for several years.

Schembri’s lawyers demanded to know where these emails came from. Edward Gatt contested the substance or admissibility of the emails, which were published by a newspaper.

The emails referencing Schembri’s and Mizzi’s companies, Tillgate Inc. and Hearnville Inc., and the attempts to open up bank accounts for them, are in the Panama Papers data, and are authentic.

Schembri said he doesn’t remember who Tillgate’s and Hearnville’s target clients were “because a lot of time has passed and that so many things have changed in the world that what was available in that time is not available now.” When asked if 17 Black was going to be a target client, Schembri said “it’s possible”.

Schembri could have referred to his own earlier public statements to refresh his memory. When, in April 2018, Times of Malta revealed the existence of an email from Nexia BT to Mossack Fonseca, Schembri issued a statement acknowledging that he had “draft business plans” with 17 Black. When testifying in the public inquiry on 14 December 2020, Schembri said he had given Nexia BT a list of potential target clients, including 17 Black, and that he knew who owned the company. (See pages 29-30 of the official transcript).

On his finances

“I cannot use a bank account. I cannot use a credit card. I cannot carry out a bank transfer,” Schembri said.

In March 2021, Schembri was charged with money-laundering and fraud. The court ordered the freezing of his bank accounts and assets. The court order applies only to assets in Malta, and not to assets in other jurisdictions.

On Egrant Inc.

In a previous hearing, Schembri said he did not know who owned Egrant Inc. In this hearing, he said the company “belongs to no one” and that it was not used.

Schembri’s claim is alternatively inconsistent and disingenuous. It is the identity of the intended owner of Egrant Inc. that is significant.

On 11 April 2016, the Australian Financial Review (AFR) reported that Karl Cini wrote to Mossack Fonseca in Panama saying that the ultimate beneficial owner for “this Panama company and trust…will be an individual and I will speak to Luis on Skype to give him more details”. (The details of the AFR report were published.)

Nexia BT’s only Panama-registered companies at the time were Tillgate Inc, Hearnville Inc., and Egrant Inc. Karl Cini discussed the ownership of Egrant Inc. with Mossack Fonseca in the same period as Schembri’s Tillgate Inc and Mizzi’s Hearnville Inc.. Both facts suggest that the companies were to be linked.

On his medical records

Schembri claimed that “[Daphne Caruana Galizia] published my medical records.” (“Inwegga meta hawn hekk tippublikaw affarijiet li lilhi hargitli l-medical records tieghi. Daqshekk ha nghid”.)

Daphne Caruana Galizia did not publish Keith Schembri’s medical records. She did not even have access to them. She published a public interest report about his medical condition and explained why in a letter to the Information and Data Protection Commissioner after Schembri filed a report against her. The reply cites judgements of the European Court of Human Rights (emphasis added):

“Somebody facing terminal illness, who is given X number of months or years to live, does not fear the prospect of investigation, prosecution, or imprisonment. On the contrary, the motivation of somebody with his mindset, who finds himself suddenly facing terminal illness or death in the short term, will be to intensify the scale of illicit activity so as to secretly stash away in offshore accounts even more in less time, leaving his family more than comfortably provided for after his death.

“The criminally or fraudulently inclined, if they are diagnosed as seriously or fatally ill, may find that they have effectively achieved complete invincibility because the law will not catch up with them before death does. They may as well do their worst at that stage, because all fear of retribution and consequences is now completely absent. Any fear they may have had of getting caught (pending a change in government and Commissioner of Police) and spending time behind bars no longer exists.

“In the context of all the above, but pertaining to the publication of health details specifically, may I refer you to the case of Standard Verlags GmbH vs Austria (No. 2) – application number 21277/05, final judgement by the European Court of Human Rights, dated 4th September 2009. This judgement reaffirms the principle that the health of politicians is a matter of public interest and concern, and that those who publish these details are thus protected by the principles governing freedom of expression.

“I should also direct you to the case of Editions Plon vs France, application number 58148/00, judgement by the European Court of Human Rights dated 18th August 2004, which concerns the publication of private health details (cancer) of politicians (Francois Mitterand). The ECHR found that freedom of expression trumps the right to privacy where politicians are concerned – and this even though the book which revealed Mitterand’s cancer was published by his personal physician, who was himself subject to the strictures of professional secrecy, making it technically a double breach of confidentiality and the right to privacy.”

On his use of a diplomatic passport to open a company in Panama

Schembri claimed he gave Nexia BT his diplomatic passport because it was the only one he held at the time.

Schembri’s testimony on the matter of his diplomatic passport is inconsistent. He claimed he only held a diplomatic passport, said there was no reason why he gave that passport to Nexia BT, then said: “If I was smart I would have given them my other passport”, then said he doesn’t know if he held another passport.

A certified true copy of Schembri’s diplomatic passport (see below), together with a “know your client” form, was included with an email from Karl Cini at Nexia BT to Mossack Fonseca in Panama. The passport copy was authenticated on 18 March 2015. Cini’s email, dated 20 August 2015, concerned the opening of a bank account in Panama. The documents are in the Panama Papers data.

Schembri said he did not authorise Nexia BT to send [a copy of] his diplomatic passport to Mossack Fonesca, and that he gave them that passport to manage his affairs in Malta.

The claim is disingenuous. Schembri said he did not question the decision to set up his company in Panama and he signed a Master Fiduciary Services Agreement on 16th June 2015 that “shall be governed by and constructed in accordance with the laws of the Republic of Panama.” That obviates the need for his authorisation.

On how the Electrogas contract was awarded

Schembri said he “cannot remember” if any steps were taken to evaluate and investigate the way in which Electrogas won the power station contract and that he doesn’t remember if it was discussed or if any internal steps taken.

There is no evidence in the public domain that the OPM evaluated and investigated the way in which Electrogas won the power station contract, nor that the OPM discussed the matter or took any internal steps. Schembri’s testimony is evidence of bad governance.

Schembri was asked whether there was a discussion about a conflict of interest when Nexia BT was also part of the evaluation committee about the choice of Electrogas, especially in light of him, Konrad Mizzi ,and Joseph Muscat all being Nexia BT clients. He said it was never discussed “ghandi ma waslitx” and he never brought it up.

As the prime minister’s chief of staff, it was Schembri’s duty to bring matters to the attention of the prime minister, such as Nexia BT’s conflict of interest on the evaluation committee that decided to award the power station contract to the Electrogas consortium. There is no evidence in the public domain that Schembri raised any concerns with Prime Minister Muscat, nor any evidence that they discussed the matter. Again, Schembri’s testimony is evidence of bad governance.

On his discussions about Electrogas

Schembri claimed he never spoke to Yorgen Fenech about Electrogas.

Keith Schembri held at least five meetings with Fenech at the Office of the Prime Minister in 2013 and 2014, according to information obtained through a FOI request. The Electrogas power station was supposed to be delivered by March 2015. It is reasonable to assume that the status of the project was discussed at the meetings. However, no record was kept of meetings that OPM officials and staff members held with Fenech. In reply to separate Freedom of Information requests for the agenda and minutes of the meetings held between Fenech and specified OPM officials and staff members, the Principal Permanent Secretary (OPM) replied “this Public Authority does not hold the requested documents.”

On his interference in police investigations

Schembri denied intervening to stop the police questioning Yorgen Fenech in 2018 on 17 Black after Times of Malta and Reuters identified Fenech as the company’s owner. Schembri says that he didn’t call Silvio Valletta to discuss Electrogas allegations. Schembri “ghalxejn qed issaqsni ghax jien m’ghamiltux dak il-kumment jien”.

The official transcript of former deputy police commissioner Silvio Valletta’s sworn testimony in the public inquiry on 2 November 2020 says that, when the police were going to Portomaso to speak to Fenech, Valletta received a phone call from Keith Schembri. The transcript quotes Valletta saying: “Keith Schembri, in a sarcastic tone said, is this what you do? Investigate people on the basis of a news report?” Schembri’s phone call to Silvio Valletta was on a Sunday in November 2018. Times of Malta and Reuters identified Fenech as the owner of the offshore company, 17 Black, on Sunday, 9 November 2018.